Period Overview - Roman

The Roman Conquest of the North-East

Although the first Roman invasion of Britain was led by Julius Caesar in 55BC this was only a brief expedition, and the Roman armies swiftly returned to Europe. The second invasion came nearly one hundred years later in AD43. The Romans quickly conquered much of the south of the England.

Although the tribes in the north-east of the country had not been defeated in battle they became allies to the Romans. The main tribe in this area was a group known as the Brigantes. This large tribe probably included many smaller tribes, such as the Tectoverdi and Lopocares. Their lands covered much of Northern England from the Pennines and North Yorkshire to Northumberland and southern Scotland. The other main important tribes was the Votadini. Although they mainly controlled southern Scotland from Edinburgh southwards, they may also have had power over parts of northern Northumberland.

At first the Brigantes, under Queen Cartimandua, were a friendly ally of Rome and protected the northern borders of the Roman-controlled area to the south. However, after a domestic dispute between Cartimandua and her consort Venutius led to civil war amongst the Brigantes, the new emperor, Vespasian, sent the Roman governor of Britain, Petillius Cerealis to take over the whole of the North of England.

Hadrian's Wall

The greatest surviving monument of the Roman period in the north-east of England are the walls and forts of the fortified frontier known as Hadrian's Wall, which runs from Wallsend to the west coast of Cumbria.

It cut across much of the lands of the Brigantes, which reached into North Northumberland.

However, this was not the first group of defences running along this line.

By AD81 the Roman army under the governor Agricola had reached far into Scotland, but by AD84 had withdrawn to a line between the Rivers Tyne and Solway. Under the emperor Trajan it was decided to use the road which ran between Carlisle and Corbridge as the frontier. This road was later called the Stanegate; its Roman name is unknown. It was already provided with forts at Corbridge, Chesterholm (Vindolanda), Nether Denton and Carlisle; Carvoran and Old Church Brampton may also have been built at this time.

When Hadrian became emperor in AD 117 he found that 'the Britons could not be kept under Roman control'. He visited the province in AD122 and decided not to attempt another invasion of Scotland but to defend Trajan's frontier. However, it was clear that a frontier which was defended by forts and watch-towers but no permanent barrier was not sufficient, so he decided 'to build a wall, eighty miles long, to separate the Romans from the barbarians'.

Initially the frontier was to consist of a curtain wall, 10 Roman feet wide, with a fortified gateway (known today as a milecastle) every Roman mile with two turrets between each pair of milecastles. No forts were planned to be built on the Wall as there were already forts on the Stanegate but before the frontier was complete a decision was taken to build forts on the line of the Wall. The forts built in Northumberland were Rudchester, Halton Chesters, Chesters, Carrawburgh, Housesteads, Great Chesters and Carvoran. The frontier was built by the Second, Sixth and Twentieth Legions.

In the central sector the Wall followed line of the craggy outcrop known as the Whin Sill but in the lowland sections a ditch was dug to the north of the Wall. The Wall itself is thought to have stood up to 5 metres in height and was made from stone cut locally. At Haltwhistle Burn the soldiers left graffiti carved onto a quarry face. Behind the Wall a further defence consisting of a broad ditch flanked by two earth banks, known as the Vallum, may have protected the rear of the frontier and marked the military zone.

The Wall may not have been built merely to prevent raids from the North. It may also have acted as a customs post and travellers may have had to pay a toll to cross the frontier by one of its many gates. One gate which was not attached to a fort or a milecastle stood north of Corbridge where Dere Street crossed the line of the Wall. Although the gate itself can no longer be seen its name survives as Portgate.

To the north of the Wall outpost forts were built at High Rochester and Risingham and a fortlet built on the site of the earlier marching camps at Chew Green. To the south of the Wall the hinterland forts at Binchester, Lanchester and Ebchester were retained to provide protection in depth. There may also have been look-out-posts along the coast.

In the AD140s the Romans decided to move their border north, and built a new frontier, known as the Antonine Wall between the rivers Clyde and Forth in central Scotland. Many of the soldiers stationed on Hadrian's Wall were moved north to defend this new boundary.

Hadrian's Wall was broken through in places, although it was not completely abandoned. This meant it was easy to repair when the Romans withdrew from the Antonine Wall in the 160s and returned to the Tyne-Solway line. Despite further campaigns into Scotland over the next two centuries Hadrian's Wall remained the northern frontier of the Empire until the end of the Roman period.

Roman Roads

The main road for the Romans in North East England was Dere Street; this is not the original name of the road, but a later name given by the Anglo-Saxons, which means road to Deira or Yorkshire. Dere Streets runs from York to the Firth of Forth in Scotland and through Durham and Northumberland next to the Forts of Piercebridge, Binchester, Lanchester, Ebchester, Corbridge, Chew Green and beyond into Scotland.

Cades Road, which runs from Sockburn to Tymenouth, via Chester-le-Street, was another important road as was the route across the North Pennines through the Stainmore Pass. This cross-Pennine road runs roughly along the line of the modern A66 and although it pre-dates the Romans, they defended the route with forts at Bowes, Greta Bridge and on the pass itself.

Roman Towns

Small towns, known as [vici] grew up around many of the forts. Some of them have regular plans and they may have been founded by the army to provide places for soldiers to spend their money and homes for the many camp followers to live. Few vici have been excavated - the best understood are at Vindolanda and Housesteads - but geophysical survey at Halton Chesters and Carvorant indicate that the vici were much larger than was previously thought.

These places were probably dependant on the Roman forts, and few survived when the Roman garrisons were withdrawn. During their life time these vici were centres for trade from all over the Roman Britain and beyond. Corbridge received pottery from East Yorkshire and Essex, as well as Gaul (Roman France), Spain, Italy and even the Eastern Mediterranean. Other goods, including wine from France and even mirrors from Germany were also imported.

Apart from the vici, there were few other towns in the regions. At Corbridge a town was built over part of the fort although it continued to be used as a military base.

The settlement at Piercebridge seems to have been asmall town. The small fort at the site was not built until the third century AD on a crossing point on the river Tees.

It may have acted as an inland port for the Roman forts at Bowes and elsewhere.

The Natives

Although the Roman army clearly had a major effect on the landscape of the north-east of England, for many of the inhabitants of the region, little would have changed. The area to the north of Hadrian's Wall was only within the Roman Empire for short periods of time and the archaeological evidence shows little sign that life changed in any major ways.

The main form of settlement continued to be small groups of roundhouses surrounded by an earth bank or stone wall. There are slight regional differences in the plans of these sites. In the foothills of the Cheviots and northern Northumberland, the surrounding bank was usually roughly oval in shape.

A good example of this is the settlement at Greaves Ash Camp. At such sites there were usually several roundhouses, often with stone foundations. Small paths and yards were scattered amongst the houses. These sites were very similar to those inhabited in the Iron Age except that that in many cases the walls and banks replaced earlier wooden palisades.

To the south of the River Coquet and into County Durham the shape of these settlements was generally slightly different; the surrounding bank was usually more rectangular in shape, such as that surrounding the small settlement at Haw Hill Camp, Kielder Water.

The people who lived in these enclosed settlements were totally reliant on farming for their livelihoods. There are few Roman coins found on native sites. Little Roman pottery was found at these villages either. This suggests that few people bought or sold things at the Roman towns and forts. About the only Roman finds to be discovered at these native sites were cheap glass bangles.

It is most likely that crops were grown in the lowland areas, whilst animals were grazed on the higher areas of land. Sometime, small settlements can be seen to sit within a small network of field boundaries, such as at Coldberry Hill, Humbleton, where there are also a number of trackways. These fields are often slightly larger than the earlier prehistoric fields.

Unlike much of southern England there is very little evidence for the existence of the type of Roman farm known as a villa. One possible site has been recognised at Apperley Dene, which was surrounded by a stone enclosure wall. Another possible example comes from Old Durham, where the remains of a stone bathhouse have been found.

A final possible example is known from Holme House, near Piercebridge. Both have small stone bathhouses. Holme House was a rectangular, stone house, with a large dining room to the south and a bathhouse to the north. South of the main building was a large stone-built circular building of unknown purpose. The whole site was surrounded by a ditch.

Religion and Burial

The Romans brought with them many new gods and goddesses, both from mainland Italy, such as Jupiter, Mars, and Minerva, and from the provinces such as Mithras from Persia and Jupiter Dolichenus from Syria.

The native population, however, was allowed to continue to worship their old deities and, indeed, many of these local gods and goddesses, such as Belatucadrus, the Veteres and Mogons, were adopted by the incoming Roman army. Some British gods had small shrines built to them, as can be seen in the rock-cut shrine to Cocidius at Yardhope. Temples to Mithras have been excavated at Housesteads, Carrawburgh and Rudchester.

The burials of the native British tribes people of the north-east of England left few traces. An unusual burial site at Beadnell included the remains of at least nineteen people and a small bronze brooch. This site was exceptional, and for the most part the dead were disposed of in a way that left no archaeological record, such as cremating and then scattering the ashes.

However, the incoming Romans brought new forms of burial with them, though they never really influenced the natives. In the first few centuries of Roman rule in the north-east, the dead were usually cremated. The remains of cremation cemeteries can be found around several Roman forts, such as High Rochester and Lanchester.

The ashes of the dead were sometimes buried in pots or stone-lined graves and often had a memorial above ground. These were usually large carved gravestones which have been found close to many of the large forts on Hadrian's Wall, such as Halton Chesters, Carvoran and Chesters.

Sometimes the monuments might be even bigger: just to the west of Corbridge at Shorden Brae was a large Roman building probably used for burial. Its walls were 10m long and it was decorated with carved stone animals. It may have been the tomb of an important Roman officer. Other burials, such as those from the cemetery at Petty Knowes outside High Rochester, include graves covered by mounds of earth surrounded by blocks of stone.

In the later Roman period people were buried rather than cremated. Sometimes they were placed in lead coffins or stone-lined graves.

The End of Roman Rule

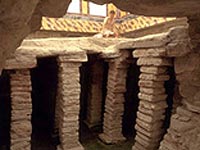

In the final century of Roman rule (c. AD300 to 410) in Britain, life changed in the north-east of England. Many Roman forts were rebuilt, with old wooden buildings being replaced by stone ones. Some barracks were replaced by new structures known to archaeologists as chalets. Examples can be seen at Housesteads Fort.

At first it was thought that these were lived in by soldiers and their families, because from the third century soldiers were allowed to marry. Previously they had not been allowed to marry until they left the army. However, this is no longer though to be likely. They certainly take up more room inside the forts, which suggests that the garrisons were smaller. Groups of irregular soldiers known as numeri recruited from along and beyond the frontiers of the Roman empire were also increasingly found defending the forts of the region.

This was increasingly a time of disorder and warfare. The tribes from northern Scotland, called the Picts, are known to have raided England heavily in the 360s. However, this increase in raiding was not just found in the north-east of England, similar attacks were occurring all over the Roman Empire.

This meant that many soldiers were taken away from Hadrian's Wall to fight in other wars elsewhere. Some soldiers may have stayed in the north, but as their pay was no longer arriving from Rome they may have deserted the army and settled down to become farmers.

There is evidence for the Roman way of life continuing for some time as people hoped for a return of the legions to protect them from increasing pressure from raiding tribes, such as the Picts and Angles.

The exact details of the end of Roman Britain are obscure and hotly debated. However, it is a testament to the ingenuity and quality of Roman engineers that some of their constructions survive so well almost 2000 years later