Local History

Ashington (Northumberland)

Ashington lies in south-east Northumberland on the north bank of the River Wansbeck. The history of this area is dominated by the development of the coal mining industry in the 19th and 20th centuries but traces of earlier human activity are also known.

The first evidence we have for human activity belongs to the Neolithic and later prehistoric period. This comes from the discovery of some worked flint tools near Woodhorn. No settlement remains are known from this period as they have probably been destroyed by later agricultural activity in the area. As we move into the Bronze Age we get our first evidence of prehistoric burial practices with a cist burial discovered at Hirst.

After the Bronze Age there is a large gap in our knowledge of the Ashington area until the early medieval period. Woodhorn may be Saxon 'Wudcestre', a place given to St Cuthbert by King Ceolwulf in AD737. Unlike many parts of Northumbria there is also evidence of an early medieval presence in some 10th or 11th century sculpture found at the Church of St Mary the Virgin. The carvings show a link with the religious community at Durham.

In the medieval period only a few villages are known in the area, for example Woodhorn and Hirst, where a medieval tower house is known to have stood in the late 14th or early 15th century. Despite the growth of Ashington, the scale of the former coal mining industry and surrounding farms, pockets of medieval field systems have managed to survive as fields of ridge and furrow. Another monument that has been recognised is a medieval rabbit warren at Coneygarth, the only one so far discovered in Northumberland.

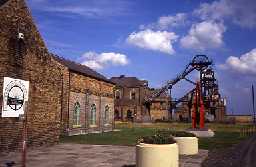

Before the first coal mines opened in the 19th century there was only a single farm at Ashington. However, the development of the coal mining industry created an entirely new mining town. By the later 19th century Ashington had grown into a large colliery village, first developing in the area north of the church and then expanding in the early 20th century in the area east of the railway line called Hirst. This scale of colliery housing was unique in Britain; nearly a quarter of all colliery workmen in Britain were employed on the Great North Coalfield by 1913 but it contained nearly half of all colliery-owned houses. From such a thriving industry, there are now no deep mines in Ashington but its past is remembered at Woodhorn Colliery Museum. Ashington is now developing new industries and services for the 21st century.

The first evidence we have for human activity belongs to the Neolithic and later prehistoric period. This comes from the discovery of some worked flint tools near Woodhorn. No settlement remains are known from this period as they have probably been destroyed by later agricultural activity in the area. As we move into the Bronze Age we get our first evidence of prehistoric burial practices with a cist burial discovered at Hirst.

After the Bronze Age there is a large gap in our knowledge of the Ashington area until the early medieval period. Woodhorn may be Saxon 'Wudcestre', a place given to St Cuthbert by King Ceolwulf in AD737. Unlike many parts of Northumbria there is also evidence of an early medieval presence in some 10th or 11th century sculpture found at the Church of St Mary the Virgin. The carvings show a link with the religious community at Durham.

In the medieval period only a few villages are known in the area, for example Woodhorn and Hirst, where a medieval tower house is known to have stood in the late 14th or early 15th century. Despite the growth of Ashington, the scale of the former coal mining industry and surrounding farms, pockets of medieval field systems have managed to survive as fields of ridge and furrow. Another monument that has been recognised is a medieval rabbit warren at Coneygarth, the only one so far discovered in Northumberland.

Before the first coal mines opened in the 19th century there was only a single farm at Ashington. However, the development of the coal mining industry created an entirely new mining town. By the later 19th century Ashington had grown into a large colliery village, first developing in the area north of the church and then expanding in the early 20th century in the area east of the railway line called Hirst. This scale of colliery housing was unique in Britain; nearly a quarter of all colliery workmen in Britain were employed on the Great North Coalfield by 1913 but it contained nearly half of all colliery-owned houses. From such a thriving industry, there are now no deep mines in Ashington but its past is remembered at Woodhorn Colliery Museum. Ashington is now developing new industries and services for the 21st century.

N13014

UNCERTAIN

Disclaimer -

Please note that this information has been compiled from a number of different sources. Durham County Council and Northumberland County Council can accept no responsibility for any inaccuracy contained therein. If you wish to use/copy any of the images, please ensure that you read the Copyright information provided.